Celebrating the Achievements of Barbara McClintock, Discoverer of Mobile Genetic Elements and Gene Transposition

In 1983, Barbara McClintock was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of mobile genetic elements.

The award came well over three decades after her first report on gene transposition, when she noted that transposons – genes which dedicated controlling elements that could move along the chromosome to a different site – were widely observable in corn.

Although her ideas were well-substantiated, they did not receive attention until the 1960s and 1970s when the same phenomenon was observed in bacteria and Drosophila melanogaster, also known as the fruit fly.

After receiving her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927, McClintock started her career as the leader of the development of maize cytogenetics – the investigation of chromosomes and how they relate to genetic expression.

McClintock produced the first genetic map for Maize, linking regions of the chromosome to physical traits and demonstrating the role of both the telomere and the centromere in the conservation of genetic information.

Mobile Genetic Elements: A Theory Ahead of its Time

While genetics as a discipline was still new in the 1920s, McClintock took to it immediately and developed a lifelong interest in the field of cytogenetics.

After visiting Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory on leave, she left her university job in 1941 to join the research facility there and focus on her experiments.

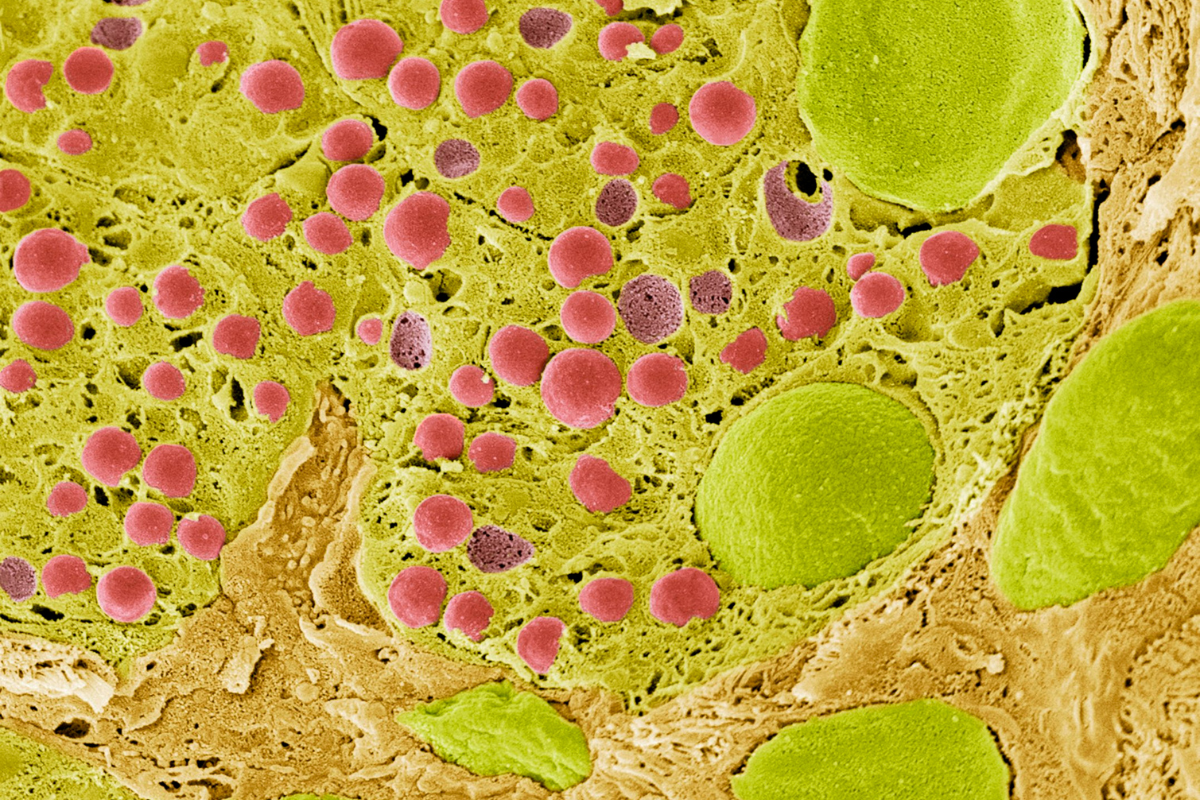

Early on her research at Cold Spring Harbour, McClintock began to study the mosaic colour patterns of maize at the genetic level.

She noticed that the kernel patterns present in the maize changed too frequently over the course of several generations to be considered mutations, containing mobile genetic elements.

As McClintock studied successive generations of maize plants, she discovered that some genes could transpose within chromosomes to activate or deactivate physical traits according to certain ‘controlling elements’.

Aware that her work departed from the accepted theory of the time, McClintock put off publishing her theories on gene transposition and controlling elements until other researchers confirmed her results.

The Belated Recognition of Gene Transposition

Eventually, she gave a lecture on her findings at the annual symposium at Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory in the summer 1951.

At the time her theories were not well received, with the audience either perplexed by, or hostile to, the implications of McClintock’s research.

McClintock was undeterred, later saying that she knew she was right about gene transposition.

“Anyone who had that evidence thrown at them with such abandon couldn’t help but come to the conclusions I did.”

In the face of significant resistance to her theories, McClintock stopped publishing and lecturing, although she never wavered in her conviction that she was correct.

After years of rebuffing McClintock’s theories, the scientific community began to come to the same conclusions around mobile genetic elements in the mid-1960s.

When McClintock finally received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983, it was a welcome confirmation of her contribution to the field, albeit one long-overdue.

Today, our understanding of gene transposition is fundamental to understanding genetics, in addition to related concepts in biology and evolutionary medicine.

Get your weekly dose of industry news and announcements here, or head over to our Omics portal to catch up with the latest advances in spatial analysis and next-gen sequencing.