Expert Opinions on Targeting the Tumour Microenvironment: Present Challenges and Future Outlook

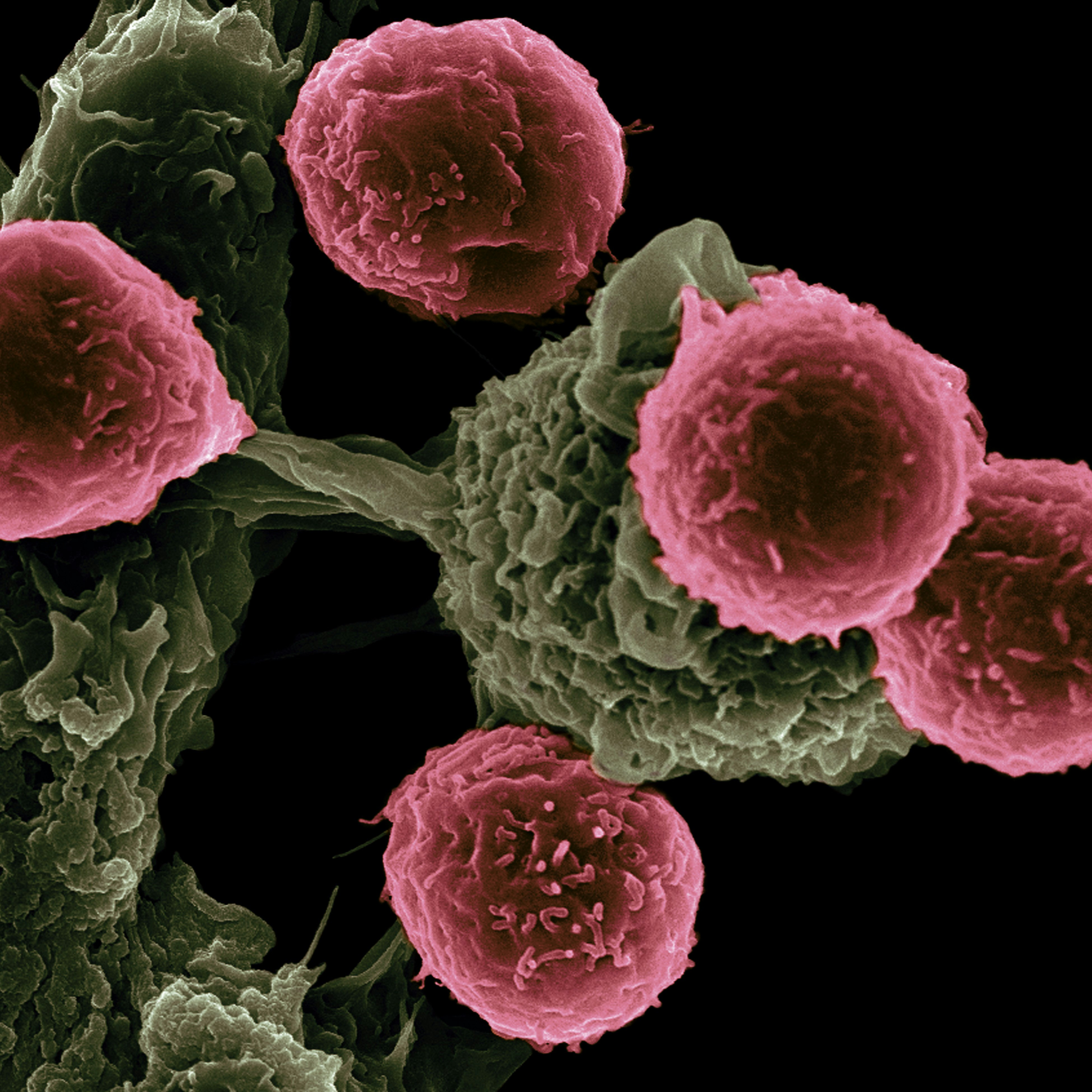

The interaction between the immune system and the tumour microenvironment is as critical to immuno-oncology as it is complex. Therefore, expanding the understanding of targets within the tumour microenvironment (TME) is a significant and developing area in cancer immunotherapy.

For this reason, Oxford Global’s Immuno series was pleased to welcome attendees from across the spectrum of immuno-oncology for an hour’s discussion on tackling and targeting the TME. Brid Ryan, Vice President of Oncology and Immunology at MiNA Therapeutics led the discussion group. Ryan formerly worked at the national cancer institute in the US as a post doctorate before running her own translational lab for eight years. Ryan’s interests and expertise focus on lung cancer; looking at biomarkers and the TME.

- Oxford Global’s R&D Key 40 Stories 2022

- Understanding The Tumour Microenvironment With Advanced Technologies

Joining Ryan as a co-leader for the session was Arcangelo Liso, Full Professor and Head of University of Foggia’s Hematology Laboratory. Liso was a post doctorate researcher at Stanford, working on cancer vaccines for lymphoma and myeloma. Now, he mainly focuses on novel targets in the TME including IGFBP6 (insulin-like growth factor binding protein 6), which is linked to fibrosis and plays a role in interaction between tumours and their microenvironment.

Extrapolating the Tumour Microenvironment’s Myeloid Component from a Blood Test?

Ryan introduced the first topic of conversation to the attendees of the session, that had to do with the feasibility of extrapolating the TME to what is found in the blood. More specifically, “is there a blood test that is able to enumerate the myeloid component in the TME?” Ryan said that from her experience, she was not aware of a blood test that was able to perform such a measurement and asked the audience if they had encountered any such test.

One attendee offered their experience and said that although they had encountered no such test, there were blood tests that were able to track the behaviour of myeloid cells in the TME. For example, blood tests are able to detect cytokines. From those kinds of tests, they suggested that perhaps a physician may be able to deduce from the specific cytokines what myeloid sub-types were present in the TME.

There were however some additional caveats to this that the participants noted. For example, due to the number of myeloid subtypes, researchers must also define the specific types that are of interest. Furthermore, their lab had been looking for specific cytokines: “this is something that we have been trying to focus on — we have not found the one specific cytokine.”

Furthermore, one attendee noted that extrapolating blood tests to the condition of the TME would be difficult as “one of the hallmarks of myeloid cells is that they change their morphology once they enter the tissue — they cannot circulate in the same phenotype as they exist in tissue.”

Ryan concurred with this particular point: “once the cells enter the TME, they completely change their phenotype anyway. Even if you could derive something from the patient, they wouldn’t necessarily match what’s in the TME when the myeloid cells enter it.”

Liso said that it would be “very difficult to imagine a test which will translate what we see in the blood into what’s happening in the tissues.” He added that pathologists “often take a snapshot of a very dynamic situation — so it’s hard to see how this could be easily translated into a blood test.”

“There was a paper which came out a couple of years ago which claimed that they had found a useful combination of markers for myeloid cells in melanoma,” Liso further recounted, adding “— but I’m not sure that this was replicated by other groups.”

Exciting New Areas in Tumour Microenvironment Research: Aims and Difficulties

Next, the group leaders wanted to hear from participants that were in the remit of computational pathology, multiplex, staining and similar fields. Ryan said that “those fields, when applied to the TME are very exciting and potentially transformational.” Therefore, prevalent questions for experts in these sectors were: What have we been able to learn from this technology? What are the current challenges with using this technology? And, if we overcome them, what is waiting in the next frontier?

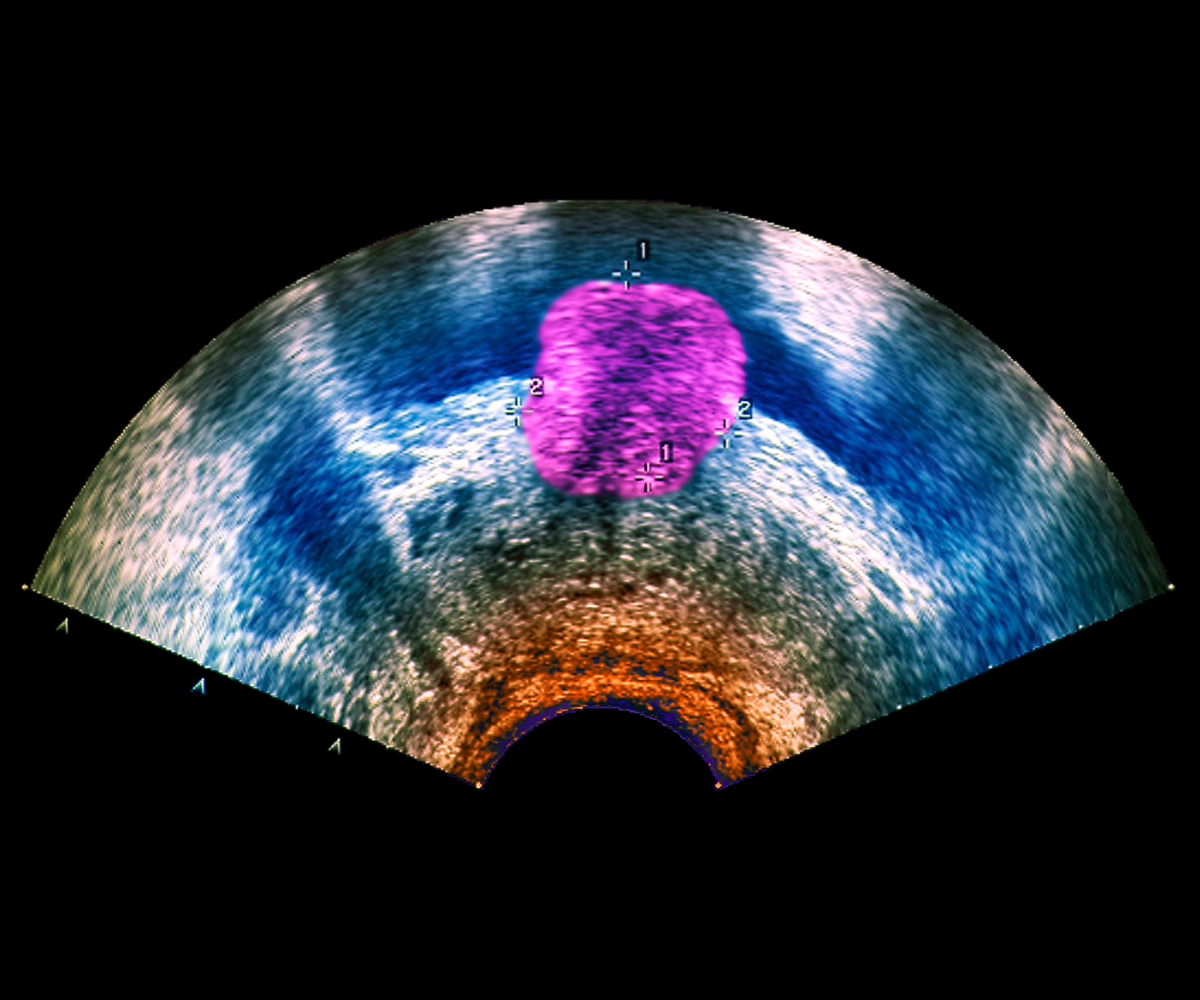

One guest said that the first concern as pathologists over the years has been the challenge of representativity of biopsy tissue when compared to the entire tumour. “We have a very small snapshot of a portion of the tumour,” they said. “Sometimes — if not most of the time — outside of its primary site, in metastatic hosting tissue.”

They continued: “Therefore, we imagine already the effect of the niche on the TME — the potential mutations that happen during that journey from the primary site to the metastatic one and the associated changes that are impacted by the host of those metastases.” More broadly, this introduces the question of what the TME is: “If we take the tumour from its primary site, it becomes quite challenging to analyse the surroundings of the tumour,” they added.

Another attendee said that they were an “absolute believer in multiplex immunofluorescence” but that at the same time, its performative potential is yet to be proven. “Five or ten years ago we would have said the same about transcriptomics and proteomics,” they said. “All technologies have been very important puzzle pieces, but none of them have provided insight beyond T cells and tumour recognition.”

As always, it was a pleasure to host yet another insightful discussion. If you would like to have access to the full recording, as well as complementary invitations to join our upcoming discussion groups, please consider our membership offerings.