Experts Discuss Developing Oncolytic Virus Immunotherapy

Oncolytic viruses for immunotherapy harness viral replication and viral gene functions to mount an encompassing attack against cancer. These viruses preferentially infect cancer cells and alert the immune system to tumour tissue to help create a sustained immune response. Oxford Global’s Immuno series was pleased to welcome three expert panellists with many more attendees to an exclusive discussion group on Engineering & Translational Strategies to Develop Oncolytic Virus Immunotherapy.

Meet the Experts

Aldo Pourchet is Co-founder of Omios Biologics. Pourchet previously helped develop the ‘T-Stealth’ oncolytic virus with BeneVir and NYU. His interest in oncolytic virus therapy focusses on manipulating the innate immune response to aid in the development of better cancer vaccines. Pourchet also works in searching for more effective disease models to better predict the outcomes of oncolytic viruses in the clinic.

David Krige is Head of Translational Sciences at Accession Therapeutics. Accession is a preclinical oncolytic virus company working on an engineered Ad-5 vector platform allowing the targeting and expression of transgenes in tumour cells. Prior to joining Accession, Krige was VP of Translational Medicine at PsiOxus Therapeutics, working on a clinical portfolio with a chimeric Ad11/3 oncolytic virus.

Abhisek Mitra is a Senior Scientist at AstraZeneca and works extensively on immune modulation for solid tumour immunotherapy using oncolytic viruses as a platform tool. His focus is to achieve a better anti-tumorigenic response and build up memory T cells. His team’s objective is to use multiple strategies including combination therapy approaches to activate both the adaptive and innate immune systems.

Where are we now?

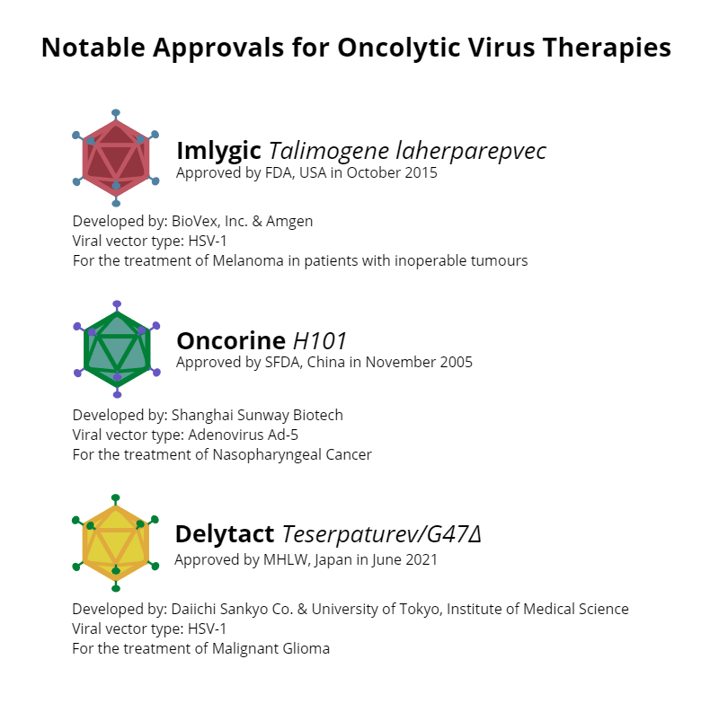

Krige introduced the topic of oncolytic viruses to the attendees: “It’s important to remember that there are three licenced oncolytic virus products currently on the market, validating the treatment modality.”

Krige mentioned a review that he had conducted into the oncolytic virus field including 27 companies currently in the clinic with candidates. “Half of them are using Adenovirus, a smaller number are using HSV and Vaccinia, and an even smaller number NDV, reovirus, coxsackievirus, and VSV.”

- Developing Novel Theranostic Approaches for the Development of Oncolytic Viruses

- Delivering Immuno-Oncology Therapies for Solid Tumours

Krige highlighted promising data from CG Oncology’s most recent phase II clinical trial. Their drug, CG0070, is a locally delivered Ad-5 expressing GM-CSF which has shown complete response rates approaching 90% in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer for patients that have failed Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) immunotherapy. “That’s double what you would expect with checkpoint monotherapy,” said Krige.

Given the many candidates in clinical trials and the promising data that is emerging from them, there is massive hope invested in the future of oncolytic virus-based immunotherapy. “We are in a good place to see the fruits of many years of labour coming out in the coming years,” confirmed Krige.

IV Delivery vs. IT Delivery of Oncolytic Virus Therapy

The first question that our attendees discussed concerned the merits of using intratumoral (IT) delivery versus intravenous (IV). IT has been the predominant delivery method to date for the majority working on the modality. Adenovirus and Vaccinia are predominantly dosed IT, with a couple of exceptions, noted Krige. “I think IT delivery is great for localised tumours and has validated the efficacy of oncolytic viruses as a treatment modality, but if you’re thinking about going after metastatic disease, you really have to go IV,” he said.

“It seems to me that IT delivery won’t cut it for metastatic disease. IV is the holy grail, but it’s clearly challenging. But to me, it’s very much worth pursuing.”

Pourchet weighed in on the topic of delivery, stressing that it was a question that had persisted for a long time in the field. While IT is the preference for clinicians, investors of programs in big pharma want to use IV as it is a better adapted delivery method for the medical industry.

However, Pourchet suggested that IV delivery may not be necessary to launch a systemic immune effect. For example, if an oncolytic virus reaches a tumour and is able to launch an antitumoral immune response which tackles the metastases in a vaccine effect.

One benefit of IT delivery is that clinicians can choose and control the exact amount of virus and co-injection combination. A problem with IV is that it often does not deliver enough of the virus into the tumour tissue. Pourchet noted that carrier cells may offer an opportunity to circumvent this problem. “A few programmes out there are using stem cells or NK T cells that are chemotactic to the tumour,” he said.

Overcoming Virus Neutralisation

Another concern that can affect the efficacy of oncolytic virus therapies is virus neutralisation via pre-existing or treatment-emergent antibodies. Mitra said whether the therapy is dosed IT or IV, neutralisation can emerge when the virus is exposed to B cells in the tumour microenvironment or the circulatory system. “Most cancer clinical trials are for multi-dose therapies, not single dose,” he added. “So with the amount of the virus being exposed to B cells, there is a good chance of the patient developing antiviral antibodies pretty quick.”

One way of overcoming virus neutralisation that was mentioned was to design the virus with its immunodominant epitopes modified to reduce the chance of the patient developing neutralisation antibodies. However, an issue with this method is that taking out dominant epitopes can simply cause new epitopes to emerge in their place. One attendee wondered whether it was possible to overcome the “whack-a-mole” dynamic of removing dominant epitopes only to find new ones showing up. Krige noted that it remains to be seen in the clinic how significant an issue anti-virus antibodies are for effective delivery of virus to the tumour.

Another important factor that affects the immune neutralisation of oncolytic viruses is the situation in the tumour microenvironment. Mitra explained that results from profiling suggest that many CD8 and CD4 T cells are virus-specific within the time generated. These findings mean that there is a high chance that the adaptive immune system works within the duration of exposure to the virus.

Pourchet added to this point, suggesting the efficacy of animal viruses to evade problems with innate immunity. “We have seen some companies using animal viruses such as Myxoma virus where there is no pre-existing immunity,” he said, adding “these viruses, being not adapted to human beings, can be very safe because they cannot replicate, and more inflammatory so potentially better adjuvant for an anti-tumour immune response.”

As always, it was a pleasure to host yet another insightful discussion. If you would like to have access to the full recording, as well as complementary invitations to join our upcoming discussion groups, please consider our membership offerings.